Relive the golden age of video games with Howard Scott Warshaw, a pioneer in the industry. As technology continues to revolutionize the world, take a step back to a time when the emergence of home video game consoles captivated the world. Howard played a significant role in this period as a legend of the Atari 2600, having created classic games such as Yar’s Revenge, the first movie-to-video game adaption Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the controversial ET.

My guest, Howard Scott Warshaw and I discuss:

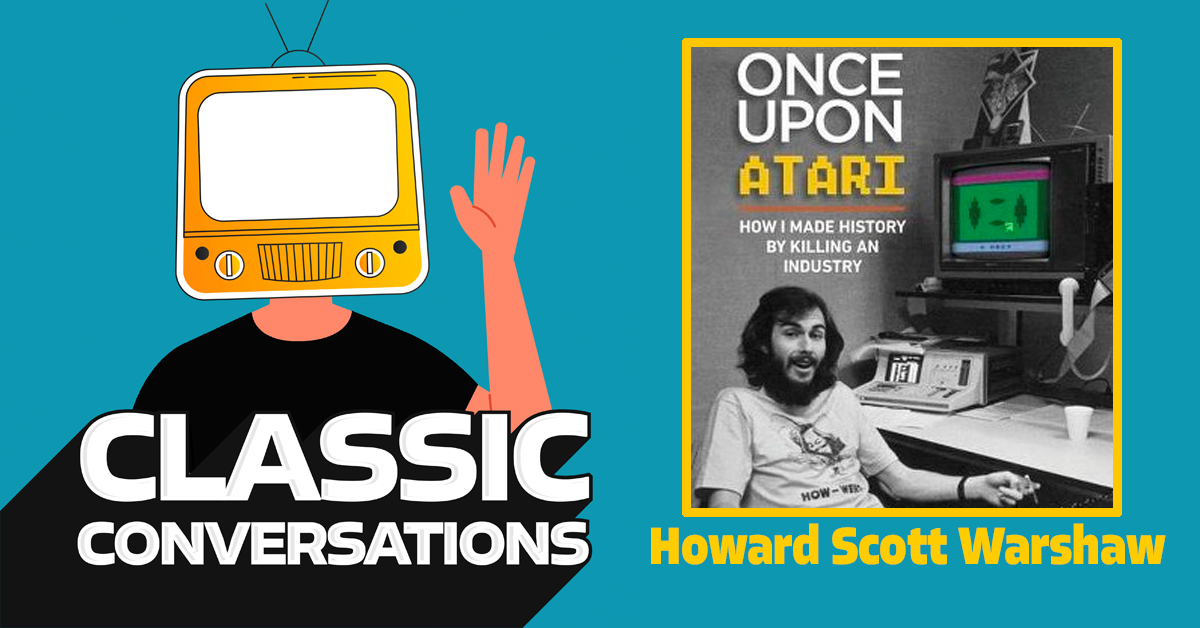

- Howard Scott Warshaw, the author of “Once Upon Atari: How I Made History By Killing An Industry”

- From Hewlett Packard to Atari: Warshaw’s journey in the video game industry

- The untold story of drugs and partying at Atari

- Discovering the magic behind Yar’s Revenge game development

- Collaborating with Steven Spielberg: The creation of the first movie-to-video game adaption, Raiders of the Lost Ark.

- Why Warshaw said YES to the controversial ET Atari game when everyone else said NO

- Inside the corporate culture of Atari during the golden age of video games

- Paving the way for innovation in the video game industry

- The significance of Easter eggs in video games and their origin

- The truth behind the ET Atari game controversy and its impact on the industry

- How the internet revolutionized video game creation and Warshaw’s legacy

- A glimpse into the future: The upcoming Yar’s Revenge sequel

- and SO MUCH MORE

You’re going to love my conversation with Howard Scott Warshaw

- Howards Website

- All about the book

- Once Upon Atari (book) on Amazon

- Autographed copies of Howard’s book for purchase

- PLAY CLASSIC ATARI 2600 online

Follow Jeff Dwoskin:

- Jeff Dwoskin on Twitter

- The Jeff Dwoskin Show podcast on Twitter

- Podcast website

- Podcast on Instagram

- Yes, the show used to be called Live from Detroit: The Jeff Dwoskin Show

CTS Announcer 0:01

If you're a pop culture junkie, who loves TV, film, music, comedy and other really important stuff, then you've come to the right place. Get ready and settle in for classic conversation, the best pop culture interviews in the world. God's right, we circled the globe so you don't have to. If you're ready to be the king of the water cooler, then you're ready for classic conversations with your host, Jeff Dwoskin.

Jeff Dwoskin 0:29

All right, Shirley, thank you so much for that amazing introduction. You get the show going each and every week, and this week was no exception. Welcome, everybody to Episode 206 of classic conversations. As always, I am your host, Jeff Dwoskin. Great to have you back for what's sure to be classic nostalgic interview for the ages. With me today is Atari 2600 game developer legend Howard Scott Warshaw, a developed Yar's Revenge Raiders of the Lost Ark EA T. Author of Once Upon Atari, how I made history by killing an industry I leave no Easter egg unturned as I dive in with Howard Scott Warshaw, and that's coming up in just a few seconds, and in these few seconds, a quick reminder episode 204 with Hollywood legend Ruta Lee, amazing stories, you love the Rat Pack, you're gonna love Ruta Lee, you love the Twilight Zone, you're gonna love rudely. Also our bonus episodes from crossing the streams, where we serve up TV binge watching suggestions, awesome stuff, but right now we must turn our attention to Howard Scott Warshaw, developer of what is considered one of the greatest games of all time. Yar's Revenge and one of the worst games of all time EA T. You may be familiar with the EA T story about all the Atari T's being buried in a desert. That's this guy. He developed that one. I were talking about that so much more right now. Enjoy. All right, everyone, I'm excited to introduce you to my next guest tare 2600 Legend braider of Yar's Revenge write it as a Lost Ark EA T saboteur and the upcoming Yar's Revenge sequel, also author of Once Upon Atari, how I made history by killing an industry in for a treat my guest today, Howard Scott Warshaw.

Howard Scott Warshaw 2:28

Thank you, Jeff, it's great to be here. Appreciate it.

Jeff Dwoskin 2:31

I am so excited to have you here. I 12 year old Jeff spent all his money, Atari 2600. And cartridges I can remember to this day writing out the business plan to my parents, I didn't call it a business plan at the time, but just saying, Here's my money, here's how I'll figure out how to pay this. This is how I pay the tax. Let's go to Toys R Us. Yar's Revenge was definitely part of that. I'm pretty sure writers and et must have been as well. And so I'm excited to talk to you about that. And the myth behind et and your self proclaimed killing of the industry.

Howard Scott Warshaw 3:07

Yep, the myth and the reality. It's all here. It's all

Jeff Dwoskin 3:10

here. So let's start with just how you got into the video game industry. At the time when you joined Atari. It's an emerging industry. It was

Howard Scott Warshaw 3:21

a fledgling industry, right? It was a new medium. I mean, this was the beginning of interactive entertainment. And I went to it most of the people who went to atari went there to make games because that's what it was all about. Except me. I always have to do things the odd way or the different way. I didn't go there to make games. I thought it was cool to make games. I went there because I was so unhappy at Hewlett Packard where I was working as a multi terminal systems engineer on some state of the art stuff that wasn't very entertaining to me wasn't very interesting. And I heard that Atari did more intense kind of programming that I was doing at Hewlett Packard which appealed to me also, I was kind of a zoo case at Hewlett Packard, I tended to act out and build a more wild than most of my programming compatriots. So I heard that the environment at Atari was much more wild and out there and place where acting out would be perceived as normal. And so that sounded good to me. And the idea they made gains was just sort of a great extra bonus.

Jeff Dwoskin 4:17

Yeah, from the book. It sounds like it was it was quite the party culture. You tell us about the use of drugs right right off the bat.

Howard Scott Warshaw 4:25

That's an understatement. I mean, there was a lot of rumors and a lot of stories about drugs at Atari and partying at Atari and stuff. So I just want to set the record straight right now there was a tremendous amount of drugs at Atari was absolutely a lot of drugs that it's alright, but the real drug the Apex High the thing you really, really chased after an Atari wasn't the pharmaceutical high. It was releasing a video game and putting a game out there and seeing it advertised on TV and being able to walk into a store and seeing your work on the shelf or seeing it on the demo says Some better still. And at one point, I actually experienced what I would call the apex Atari high. And that was going into a store. My game is on the demo system, and I got to see several kids fighting for the controller for the chance to play the game, it doesn't get a lot better than that at Atari,

Jeff Dwoskin 5:18

that has to be an incredible moment to be able to kind of see it in action, because that's, that's unfiltered, that's real. It doesn't get realer than that people can blow smoke all they want about anything. But when you're watching some kids fighting over that demo station at Toys R Us or wherever you're at, like that's the real deal like that,

Howard Scott Warshaw 5:36

that was arriving that was being there. It was a true moment. And it was an amazing feeling. Totally exhilarating. Atari was full of moments like that Atari Atari was a very, it was the most emotional place to work that I've ever been. But it was a full range of emotion. The thing about atari is you can have an amazing day one day and be on top of the world. And you could come in the next day and not be sure if you're still going to be working there. By the end of the day. It was an extremely volatile environment where anything could happen and anything did.

Jeff Dwoskin 6:09

That's crazy. I did have one other question about that demo station. Now, did you ever approach the kids and kind of maybe just got out? Or is it Did you ever like tip him off who you were like that you're kind of observing and and break that fourth wall if he Well,

Howard Scott Warshaw 6:23

I thought about it. I did not do that though. I would go up to the kids and say, Hey, what's the name of that game? And see if they knew it? And I'd go is that any good, you know, and hear their feedback. But I would not go to them and say, Hey, I'm the guy who did that. I did have an experience like that. Once though, that was very interesting. At a video game shop, there was one of the conventions going on. And when I go around to the booths at the conventions, if people have old 2600 cards, I was asked if they have my games. And I went up to one booth at a show and I was speaking at this show. It was a little while before my talk, I went to one of these booths. And I said hey, do you have any Yar's Revenge? And the guy says to me, yeah, he goes, in fact, the guy who made the game was just here a little while ago. I said, Yeah. And he goes, Yeah. And I said, You know what? I said, I don't think that's true. And he's like, really? I said, Yeah, I said, Because I'm the guy. And I showed him my license my driver's license. I said, I said, I'm the one who made this game. I said, So you're telling me somebody's going around saying they're me. That was an interesting I was, it was a very unusual form of identity theft that I was subjected to. And it was quite a weird moment, a weird

Jeff Dwoskin 7:36

moment, but also maybe a little surreal. It's, I guess, in a way, an honor that someone would think it cool enough to be right. Yeah,

Howard Scott Warshaw 7:43

I was just glad he wasn't up on the stage talking when it was my turn to go. Yeah, now when I did open this talk with that story, it was interesting, and nobody identified themselves as the person who was doing so no one wanted to come clean with that one. No, taking credit was a big issue at Atari, though. But it wasn't

Jeff Dwoskin 8:00

always the way right. Like you hit your initials in your games, but you were one of the first people that actually get credit for author credit for an Atari game.

Howard Scott Warshaw 8:11

The truth is, I am the only person I think who ever got author credit on an Atari video game, because it was Ataris have vowed policy to never give programmers credit. They wanted it to be an Atari product other like Activision and Imagic. The other game companies, they made it a big thing about who did this game because they wanted to have fan followings. They wanted people say, Oh, you want a David Crane Game or you want to rob Phillip game. But Atari didn't want to do that. But I actually and this is what I do. I have ways of creating messes that people have to figure out what to do with because I always create new situations. What I did with Yar's Revenge was I invented the backstory. No one had ever really done a backstory for a video game before. And I wrote a backstory for Yar's Revenge in addition to doing the game, and so and they decided to do a comic book to illustrate the backstory. So they don't have credits on the cartridge, but they had to have credits for the comic book, which went out with the product. And one of the credits on the comic book was the game programmer. So I actually got my name. I was credited as the game programmer in an Atari product that went out. It's the only time it ever happened at Atari. Even my subsequent games did not. I credit in it. It was just it was amazing, but I am I think I standard is the only Atari programmer ever to have been credited with their product. That was kind of cool. That is really

Jeff Dwoskin 9:35

cool. Yeah, so Yar's Revenge backstory, Easter eggs and a pause mode

Howard Scott Warshaw 9:40

Pause mode. Yeah, nobody had a pause mode in BCS game before that, you know, it just seemed like a nice way to go. If someone's going to play a really extended game. You shouldn't make bladder control one of the parameters they have to master to do well in the game. That was my feeling

Jeff Dwoskin 9:55

right? If you don't if you're not trying to get extra quarters out of someone, there's no is no answer. incentive to get them to knock?

Howard Scott Warshaw 10:01

Exactly, exactly. I mean, a lot of the thinking about making VCs games with any media, right, it was home games, video games was a new medium. And then home games was a new medium beyond video games. And the thing is, with any new media, what we always do is the first thing we do is we copy everything that worked in the previous media first, that's the first thing we do, right, the first TV shows were just radio shows with a camera in front of them. People didn't know they didn't have the killer app yet. Right, right. And so the first thing they do with home video games is copy coin op games, and coin op games don't have pause, because you don't want to stop someone pumping quarters in a machine. It's ridiculous, but pause and a coin off game. But I just realized we were making home games, we didn't have the same restrictions. And that was both my benefit and my poison at its heart. Because the kind of thinking I would put into a game demanded more up front of players, the credo at Atari was easy to learn tough to master. That's what a video game has to be. And it's true that a coin out game has to be that has to be easy to learn and tough to master. But the easier you make a game to learn, usually, the more shallow the game is going to be, it's hard to put a lot of depth into something that's very easy to acquire, it can be done, you look at games like chess, or go or backgammon, those are pretty easy games to learn. And they're really deep games, they have a lot to them, right. But that's three games out of the history of gaming, that really have that most games require a greater entry cost in terms of learning. And my feeling was Why do easy to learn tough to master, when you could make a little tough to learn and tough to master. And then you can make a deeper game. Because if I can ask more of a player to learn up front, I can give them a deeper and more complete game experience. So I did that. Of course, not all players like that, because a lot of players do want to just pick up a game and roll with it and not have to learn anything or read anything to go. And some of those players. They weren't my kind of players. Those were, you know, they didn't necessarily appreciate what I was bringing to a game.

Jeff Dwoskin 12:05

So right out of the gate, though, at Atari, you adapted that unique personality that you mentioned earlier that you had a heel Packard and they asked you to adapt, like you said, moving from the old medium to the new star cast, which was a coin game. And this is what eventually became Yar's Revenge. But you're like, Oh,

Howard Scott Warshaw 12:23

well, the funny thing about atari is that, I mean, because I was pretty much an iconic character at Atari, I think that's safe to say. But what a lot of people don't know is when I first after my first round of interviews with Atari, they rejected me, they weren't going to hire me. So I almost didn't get into Atari. But I wore them down and kept pushing. And I begged and pleaded with them to give me a chance. So I took a huge cut in salary and probation. I came in on a totally probationary period, I'll just let me do anything. Let me just give me a chance to show you. And so they give me a first assignment, which is Starcaster convert it. And the first thing I come back to say, You know what, I don't want to do this. I don't think this is good game to do. But I did tell them you know, I don't think it'll work. I think this game is gonna suck as it is on this machine. And I explained why. And then I said, here's the game, I think that would not suck and explain that and lay that out. And I was lucky they let me go ahead and do it. That is what went on to become Yar's Revenge. But Yar's Revenge almost didn't happen. I almost didn't happen.

Jeff Dwoskin 13:21

Talk to me about the process of building Yar's Revenge because I think it's it's important to understand the background and the process of creating the most successful and one of the most revered games of all time later when we talk about et and it's

Howard Scott Warshaw 13:38

another revered

Jeff Dwoskin 13:41

for a different reason. I think the contrast of understanding the right way to do it,

Howard Scott Warshaw 13:45

right. It's a contrast of the notable and the notorious for sure. So with Yar's Revenge, I mean, it wasn't Yar's Revenge Originally, the naming of Yar's Revenge is a whole nother story. But originally when I set out to make a game, I didn't want to just make a game, I wanted to make a calling card, I wanted to make a splash, I wanted to do something that was going to introduce me to the gaming the game creating community in a way that was that was significant. That was profound. That was my goal. And also to try and do things that people hadn't seen. I wanted to prove I could innovate, that I could step onto this machine and show people something really do something worth looking at. Because most people their approach to a video game, which makes sense is it's a program it's computer program, you write code, and you're going to write graphics code that's going to manipulate images on the screen. And that's the way people think about it. Most game programmers think of a video game as something that's on the screen. That's what they're thinking. And that's not how I think of it. I think of a game as taking place in the mind of the player. So when I'm programming when I'm actually writing code, what I'm doing is I'm organizing stimulus, both audio and visual, that's going to create some sort of synaptic response. It's going to make something happen in your brain that's going to make Make you feel a certain way, and that's going to be interpreted as fuck. That's the way I look at video games. That's one level of the other level of it is I don't approach it as a tech person, I approach it as a filmmaker, because I love films, I love movies, TV, all that stuff. Just love it always loved it. And so when I think of a video game, I think it's a broadcast medium. And so I want to make something that just is worth consuming. It's an exciting piece of media. So these are the things that I brought to it. So instead of just thinking, what are some rules and what's a game? And how do you play it, the first thing I thought of was, how can I put something up on this screen that's going to call the people that's going to people are going to see it and go, Wow, what's that? So I started right off the bat with animations and some glitter effects and some interesting things. And I was trying to do something that was bang for the buck, right to maximize your bang for the buck. Because the 2600 is also an incredibly limited resource, you only had a few kg of code, and 128 bytes of RAM. I don't know how tech your listeners are. But that is not a lot of resource to work with. And within that you have to do everything, which is a great challenge. It's a pain in the ass on one level, but it's a huge challenge. And so I set about doing what I do, which is to look at this stuff and just say what can I do? What can I do? That's cool, what's something that would be fun. And I came up with I started with an animation I came up with that glitter zone and I had I had blocks of things that are moving and rotating and running around. My feeling was everything has to move every animated color in addition to animating shapes and motion and nothing standstill. Because the thing is, if anything stands still it's dead. You know, there's a saying they have in the jungle is that if it doesn't move, it's food. And that's the thing is I want it to be that the player has no respite knows no break, even though there's Pause mode, right? It's like you have to move to stay alive. It's like a shark. And there's constantly threats and constantly color things going on. And I also added a layer of soundscape because in filmmaking, you know, you can save a lot of money by using sound effects, instead of actually getting the actual equipment in place to do it. You know, if I play a foghorn, that's a lot cheaper than actually having to rent a luxury liner. On screen.

Jeff Dwoskin 17:21

Sorry to interrupt have to take a quick break. I want to thank everyone for their support of the sponsors. When you support the sponsors. You're supporting us here at Classic conversations. And that's how we keep the lights on. And now back to my magical conversation with Howard Scott Warshaw, we're going deeper into the magic of sound and video games. And we're back,

Howard Scott Warshaw 17:41

right so I use sound not just to be a bleep bloop to mark events in the game, I tried to use sound as a soundscape to dictate mood and build tension. So there are things there are subtle changes in the sounds of the game as you move or as you do certain things or that warn you that some danger is coming up. And I think that was a big part of the impression of the game. A lot of the things that were in the game, I was able to utilize those in ways that people just hadn't seen before. So it was exciting. And it was exciting for me as a newcomer to go in and do some stuff and have people who are veterans on this machine go Well, how'd you do that? They're like, well, that's cool. That was exciting.

Jeff Dwoskin 18:16

That is exciting. And I have a question our when you get to atari this is this is your first game. So you don't have like all this background doing it and all that kind of stuff that you said, Oh, I did this last time. I'll do it. What were some of the inspirations that you kind of saw like, oh, that thing I'm just to make this that thing I Missile Command, right? Boom, I've what if I did this way? You know, what were the some of that like glitter is of inspiration, whether I guess from Atari, or anywhere that you might have got it said I can I can visually adapt these concepts.

Howard Scott Warshaw 18:44

Jeff, that's a really cool question. No one has ever asked me that before. So I have to say, honestly, the inspirations that I got were not very much from other games. They weren't even from the game I was supposed to be copied. The inspirations that I got were more from movies, it seemed that I thought were particularly good, and from the machine itself. So it wasn't like I wouldn't say no, some people would say, here's what I'd like to do on the screen. How can I do that on this machine. And instead, what I would do is I would come and look at the machine really intensely from different angles in different ways. And just try to notice different weird bit patterns or things and I would say what can I do on this machine? That's Nobody's expecting me to do what's something weird I can do on the machine? And how can I make that part of a game? Right? It's sort of like the inverted thinking. That's how he came up with the ion zone, right? It's like the ideas you know, we have very little space on this machine, very little space and most graphics, you have to take up memory space to put the actual bit patterns for the graphics in and then you have to put them in the registers in the graphics registers as you go down the screen. And that's how you make graphics appear on a screen in the 2600. But it costs you a lot of time plugging the things in the right registers and picking up the data and the data takes up space itself room. That's precious room. So I started to think, How can I make graphics that don't need graphics maps. And so what I did with the ion zone is, instead of using extra graphics to create that I use the code, I mean, I already have the code in the card, the programming code has to be there. So I just and it was sort of like was a semi randomized pattern, if you look at the bits in computer code, so I just grabbed the code, put that in the graphics register, and then put the same thing in the color register. And it automatically randomized both the graphics and the color and made this great glittering effect. And it cost me zero memory, rather than actually save time in the coding. So that's the way I would say, it's like, what can I do that's cheap, programming wise, and that has some real impact stimulus wise on the screen. That was what I look to for inspiration. And then when I see that and I make something happen, I say, okay, so what can I do with this to create a game out of it, now I have this cool thing, but I don't know what to do with it. So now I got to figure out some meaningful way of incorporating it into some sort of game action. And that's where the real challenge is.

Jeff Dwoskin 21:12

I love that very innovative, I guess there's some benefits to being first you can kind of that's how you, you become the trailblazer. And people start imitating you and stuff like that. Oh, yeah, I got that from Howard stole that from our,

Howard Scott Warshaw 21:24

it's true. And whenever we would develop a technique, we would publish it to the other programmers in the group. It was a very congenial environment, people were happy to share and share their techniques and ideas and things like that. And it meant something to be able to create something new and share it with the others.

Jeff Dwoskin 21:41

That's awesome. So the whole combination of controller the whole, it's a whole thing right now, when you as you were describing the movie, that's I think how I am when I play a game. So I imagine all people are, at least most people are, it's like you're becoming one with this game. And that's, that's how you get so intense with it and have to start right over it becomes like this crazy part of you while you're playing it very much. So

Howard Scott Warshaw 22:04

alright, so

Jeff Dwoskin 22:05

you name it, you name the game, very clever how you name the game. I love that story. When you talk about the process you talk about first playable is sort of like the first kind of milestone where you're playing. And it's a version of the game without final graphics where people can kind of get, it's basically a rough draft right of the beta version, alpha version, maybe even like even before that I don't

Howard Scott Warshaw 22:27

write you see, it would definitely be pre alpha is first playable is the first time you can check the rules of the game, and the first time you can get the experience and the feel of the game. It's a very important milestone in the game. When I got Yar's Revenge to first playable, it sucked. And that was kind of a devastating experience. Because yeah, you wanted to know about the process of it. So I had some ideas. And I had the general direction of the gameplay, of course, I mean, I had some idea of it. And I was very focused on the sizzle and trying to make things really shine and look cool. I got all the pieces together, I got some of this as a win. And I got it to the point where I could start to actually play and experience the game. And it wasn't very good. It was cumbersome. The The only thing I really kept from Dark Castle was the controller scheme. It had the classic asteroids thing of you know, you rotate right laughter You push forward and you control your momentum. Because I needed one extra way to handle the joystick and joystick back would have been able to launch this cannon was Orlan cannon, which is essential to win the game you can't really get anywhere in the game if you can't launch that weapon. So I was kind of married to that Controller Configuration. And as I started to play with that, it was horrible. And most people who picked it up didn't like it every once in a while, there'd be one or two people who liked that controllers game and they enjoyed it. And they moved around. And it was fine. But it wasn't intuitive. And it didn't feel good. And it really dragged the whole game down. And now I'm thinking, Oh, God, what do I do? What do I do? And someone suggested that I just start moving the player directly, instead of doing the right left, rotate, just move, you know, just move directly. And I thought that's a good idea. But if I do that, now, I have no way of launching the candidate, you know, the key weapon in the game that you need to win the game. So I was very resistant to doing that. But at one point, I decided you know what the hell you got to take the feedback, you got to listen to the people. You got to follow through. And so I did try that motion scheme. And it did feel great. It really It not only changed the field, the game was super positively it was also easier to implement because I didn't have to worry about inertia and momentum. You just go or stop. I just made it an instant thing. And so it actually saved me code space. But now I had the problem. So how do you get a cannon? How do you get the cannon because the fire button is already used for your regular weapons. And then it occurred to me, you know, when you have to take something off the controller, you need to put it into the gameplay and that was a huge turning point in the game because what I did was I fixed it so that the way you get the cannon is either by eating parts of the shield or by touching the monster the code time and that's great big cuz in order to get the weapon to kill the monster, you have to approach the monster and increase your risk. So it has that thing of like, you know, you need to take greater risks to get greater rewards, which is always a good correlation in a game. And it also made the game more dynamic. It forced you to move yourself around the screen more and introduce more motivation because one of the things I didn't like about Star Castle was the visual focus and star Castle is always locked in the center of the screen. And that's I think that's monotonous. I want it like in filmmaking, what I said is I one thing, there's a great rule of filmmaking, they call it up, down, right, left, up, down, right, left you people, you know, you never notice like act really good action scenes in movies, a lot of times, what you'll see is they start from one place, and then another place, and it's like, up, down, right, left, up, down, right, left, somebody comes in from the top of the screen, and somebody comes in from the bottom. So they comes in from one side comes in from the other side. Star Wars is the classic example of that. So I put that in the game, I thought, Well, what do we do so to really do well, in Yar''s, you have to be running the player vertically, either up or down, and then there's the missile trailing you from the monster. And then you have to shoot something from the left side in, and the monster is going to come from the right side out. But all this animated motion is going on in the periphery of the screen. And every once in a while, they all converge into the corner of the screen. And visually, I just think that's hot, right? It's just an exciting thing. Because you have vertical motion, you have horizontal motion, it's all going on. And so it's a symphony for the eyes and the ears. And that's what I was trying to do. And once I made that change, that serendipitous change, the game came to life. And now suddenly a game that everybody thought was cool looking but didn't play well. Now, suddenly, people love. And it was an interesting transition, you know, suddenly I have the I have the hot game, I have the game that people love. And that was super exciting. So what do you do with that?

Jeff Dwoskin 26:47

You put it into a mindset and mindset of testing. Why? Why were they so nervous about your game?

Howard Scott Warshaw 26:53

They weren't that nervous. There was it's an interesting thing. But in the entertainment business, which is I believe, is what this was, there's an interesting phenomenon that, you know, success is great. Everybody wants to succeed, but everybody wants to success to be theirs. And some people don't want to success to be someone else's. And I think that was at the core. Because what I kept hearing, it's true that Yar's Revenge was the most tested game in atari history. No game had ever gone through that much testing. And why does the game keep going through testing? Either you tested and the testing isn't good. So you stop testing and you need to work on the game, or you test the game and it does well you release it you don't need to keep testing. But Yar's Revenge kept getting tested. And what I found out was there was someone there was this, this one person who kept saying the game isn't okay, everybody loved the game all day, every time they tested, the game would do great. But there was someone who's saying there's still problems. There's still some playability issues. We're not real. I'm not really sure this game is working. I didn't know who it was. But it was weird. And they were obviously in enough of a position to cause these delays. So they tested it almost as long as it took to make the game. And it all came down to the big play test, the ultimate play test the typical tests or focus tests where you get eight to 12 people and you give them pizza, and they play the game for a little while. And they give you feedback on the game. And we had done several focus groups, and they all went well. And every time they do a focus group, because this is my first game, right, right. You're not really in the club until you release a game. And I wanted to join this club. I wanted to be an Atari game designer that was that was important to me to arrive in that place. And so they test the game and the test would come back great people like it. Okay, let's release it. Okay, here we go. Oh, no, wait, there's there's some concerns about So okay, so we'd run another test. And how did this all this went great this way, because I was at every test, right? I would be behind the two way mirror watching everything. And it goes well, okay, here we go. That it works. It's fine. Oh, no, we're not going to release it yet. So finally did a play test. They do a play test where over 100 people come in over the course of a weekend. And they play two games, they play the test game, and what's called the control game, you know, there's a game they're going to compare it to. So play tests are all about the control game, like what's the game you're going up against? So I'm waiting to hear so what's it going to be? You know, what's going to be if they picked Missile Command, they picked 2600 Missile Command, which was the absolute best game on the 2600. At that time, I believe

Jeff Dwoskin 29:20

that's coin and Best 2600 Game.

Howard Scott Warshaw 29:23

Yes, it was a killer game. And it was an excellent implementation done by a very good friend of mine, Rob Phillip, and I thought, no, no. They're trying to kill me. They're trying to kill the game. Somebody

Jeff Dwoskin 29:36

doesn't like our job. We got to figure out who it is. It's like

Howard Scott Warshaw 29:39

something is up here. Yeah. And so and so I flew to Seattle where they were doing the test and I was in the pit you know, in there watching all the stuff going on. And the play test is not as interesting to watch as a focused as because it's just people sitting and playing filling out sheets. But what's interesting is reading the sheets and when the sheets started, the first sheet started to come back in the first sheet I looked at yours was just trashed. They absolutely trashed Ya's Revenge on it loved missile commando thug. Yeah, this is brutal, brutal, I'm gonna have to sit through a whole weekend of this. But it turned out that was the worst sheep for Yar's. For the entire weekend, I happen to see the worst one first. And it got better and better and better. And when the smoke cleared at the end of the weekend, Yar's Revenge beat Missile Command. In the play test, it actually beat the best game on the system and set a record for play test results. And so it's like, okay, so how can we now release it? So finally, whoever was complaining, they lost credibility at that point, I think and, and the game did go out. Finally, it would have been fine. If it would have gone out five months earlier, I would have been okay with that. But that's not how it went.

Jeff Dwoskin 30:47

It's like a Steve Kornacki thing going on. It's like, Wow, that really returns around. But don't worry that these counties haven't come in yet. And there.

Howard Scott Warshaw 30:56

We still only have 67% of respondents at this point. But we're declaring it we're declaring. It's, yeah, I'm a I'm a staff jockey. What can I say?

Jeff Dwoskin 31:06

Alright, so this becomes your first million dollar seller and finally gets released your first of many million dollar sellers. You're a million dollar

Howard Scott Warshaw 31:14

million units sellers. Yeah. I mean, it's Yar's Revenge sold a million units right or sold a million units, even et after return still sold well over a million units. I think I'm the only game programmer ever, I think who can say that every single the only VCs programmer for sure that every game I released was a million seller. That

Jeff Dwoskin 31:33

is incredible. Let's talk about Raiders. The Lost Ark. Let's do our guy who loves movies. Where's the Lost Ark? Right? June 12 1981. It gets released. You were picked to do this game. And you got to meet with Steven Spielberg.

Howard Scott Warshaw 31:46

I didn't just meet with him. I had an interview with him right? Because Steven Spielberg had to choose who was going to be the program. So whoever was going to do the game had to get cleared by Steven Spielberg. So I did guys, I flew down to wonder studios in LA, got to spend a day on on the lot of wonders. That's a great story that's in the book about how I arrived there for a 930 meeting and found out it got rescheduled to 330 in the afternoon, but that means I got six hours to go around on escorted were in our studios. And that was quite an adventure. And then I get to hang out with Steven Spielberg my idol, but I'm being interviewed. Now he's interviewing me to do the first movie to game conversion ever. No one had ever done that before. But I think the thing that claims did for me was when I called him an alien. I actually explained to Steven Spielberg my theory about how he is actually an alien part of an alien advanced team preparing Earth to receive the aliens and just want to tell them what a great job he's doing. And now it's going well, I really think that might have been the thing that actually got me the opportunity to do the game. And that was my net game Raiders, the Lost Ark, that was a grueling 10 months.

Jeff Dwoskin 32:53

So when I think Raiders Lost Ark, you being a movie fan adventure games, makes a lot of sense to create the Indiana Jones experience. I mean, you must have been over the moon, I'd have a million questions on how you could even get any words out in front of Steven Spielberg at that moment in time. It just seems like I'd be like,

Howard Scott Warshaw 33:14

No, I wouldn't. Over the moon except we couldn't get the SKG logo shot, you know, the moon thing up there. So I couldn't quite go over there. That would have been good. But I was it was an amazing thing to be able to deal with Steven Spielberg, you know, look at him. He wasn't very involved in the game development. I mean, they just basically let me go and make the game. But I got to meet with him. Occasionally he would come up to Sunnyvale. And we would have lunch and chat enjoyably very cool guy, very cool guy. And the thing about Raiders of Lost Ark is it really does lend itself to a video game. It's a great movie to do a game from because it has lots of challenges. It has lots of set action pieces, and it has a through line, you know that you work your way through to get from the beginning to the end where you want to go. So it makes a lot of sense for an action adventure game. And so the designing of the game wasn't that hard to do along the way. It was just, it was a lot of work. It also that was my first adventure game. And there's a big difference. Action games and adventure games are super different from a designer's point of view. And that is that an artist thinks this is kind of an interesting thing. We'll see if anybody else thinks it's interesting. The interesting thing about is to me is that an action game the person who's making the game can experience the game just like any player, if you don't have special tricks and things hidden in it, you know, you play the game, you set up the parameters, you play the game, you tune the game, but you can have the players experience I can understand what it's like for a player to play the game with an adventure game where there's secrets to unlock and things you have secret knowledge you have to discover along the way. If you're the person who's creating the game, you already know the secrets you can't know what it's like to not know the secret and then try and figure out the secret. So when you're making an adventure game, the designer can never Have the players experience right? Only in an action games can you have the players experience? So when you're designing and tuning the game for an adventure game, what you need is a sort of infinite supply of innocent people who are willing to come in and try it out and watch them do it and gauge it yourself that way and see how that is. And it's so it's a lot more work. It's a lot harder to tune and adventure game than it is an action game. But we did it Raiders went well,

Jeff Dwoskin 35:26

very well. Why does the process similar to Yar's? I mean, just in terms of like, the milestones and the time that you had to build that you'd say,

Howard Scott Warshaw 35:35

yeah, it was pretty similar. There wasn't a set timeline for it. It was just, you know, work on this until it's a good game. That was basically the rule at Atari. You work on it till it's a good game as licenses became more prolific that got replaced by work on it until your schedule is over. Then make sure you release it because there were timing windows to be hit at that point. But when I did Raiders, it was just God make a game and I set out to make the biggest adventure game that the 2600 I've ever seen.

Jeff Dwoskin 36:01

And your book he talks about how Raiders is kind of forgotten game

Howard Scott Warshaw 36:05

it is Raiders fell in a notoriety sandwiched between Yar's Revenge and et

Jeff Dwoskin 36:10

you just you had so much different layers of success on either side. So it's interesting because I like was digging around while I was preparing to talk to you and you know, there's all these simulators online so you can play all the 2600s online lesson around with them again, it was kind of fun to to relive that the one flashback which isn't a Howard game was when you guys you talked about the adventure game and that Easter egg, man I was I did that every day.

Howard Scott Warshaw 36:35

That's the original easter egg. I mean easter eggs is something that I kind of perfected. I really look to elaborate the science of doing easter eggs, but I did not invent easter eggs. Warren Robinette who did the adventure game, he invented the Easter egg. But the Easter egg I took easter eggs to a marketing approved hook that you could talk about in manuals and advertise and make it you know, a little extra something for the game. I always thought it was a great marketing hook. That's not how easter egg started that Easter egg started. Remember how I told you I was the only programmer who ever actually got credit in a game? Yes, that's where easter eggs come from. They're about credit. More specifically, they're about proving authorship. Here's the idea. Atari does not want anyone to know who did what game. Okay, so I do a couple games for Atari. Then I go interview somewhere else and they go What have you done? Oh, I did this game for Atari. Really? Yes. Sure. You did? Like no, really? I did the game? Well, we don't believe you. Okay, so how can I do it? They won't if they call up Atari atari is not going to tell them who did the game. There was this problem of like, how do you get credit for your work. And so what Warren did was he thought, I'm gonna put something in the game that's very hard to find in the game. But it's not just anything, I'm going to put in something that identifies me as the author of the game. And so if it ever comes down to an issue of authorship, if anyone ever questions, you know who made a game, there'll be I could, I'd say just pull out the game. Let's take a look at it. And I'll show you something that will prove beyond a shadow of a doubt on the author of the game. That's where easter eggs come from. They came from a lack of trust between engineering and the company. Right? It's a corporate artifact, you could say, that's where easter eggs were born.

Jeff Dwoskin 38:19

That's brilliant. That's, that's a that's an amazing way to do it. And it's

Howard Scott Warshaw 38:24

it brilliant. It's a beautiful way to do And originally, that's what I did. I had an Easter egg in that no one would have found accidentally, but you could get there. I could get there. And then But then I thought you know what, let's make it a bigger deal. So I went and talked to marketing and tried to talk them into the idea of promoting easter eggs instead of making it something they're trying to avoid, you know, for the authorship thing. And fortunately, that worked. I think I was one of the also one of the only engineers who ever thought hey, let's talk to marketing. That was not a common thing to do.

Jeff Dwoskin 38:54

Man that was that's a rabbit hole.

Howard Scott Warshaw 38:59

You're right there.

Jeff Dwoskin 39:00

So alright, so I suppose you your buddies are Spielberg Raiders Lost Ark, your second big hat million. And then lo and behold, Steven Spielberg releases more movie magic, right? June 11 1982, the movie is released to the wonderment of the world, probably one of the most adored emotional stories ever. And then you get a call on July 27 1982, not just shortly after that, and this is where the infamy part of the story kind of starts.

Howard Scott Warshaw 39:35

Very much so yeah, yeah, they wanted me to do the E T game and it wasn't so much that they wanted me to do the T game. It's that I was the only person on the face of the earth who was willing to say I will do the video game because it came down with a five week schedule. Now. You know, Yar's Revenge for example, took seven months to develop. Raiders of the Lost Ark took 10 months to develop and those were typically Gaul development times for VCs game no one had ever done a VCs game in less than five or six months at the absolute minimum. And this was five weeks was all that was there. And so I get a call in my office one day from rake is our my boss's boss's boss's boss's boss. That doesn't happen very often. It's like, what's up Ray? He's like, hey, we need we need et for September 1. Can you do it? I said, Absolutely. I can do it. Absolutely. I was super confident. I wanted a mountain to climb. And it was funny because I thought absolutely, I will do this. I will create a game in five weeks. It just seems like a cool thing to do.

Jeff Dwoskin 40:38

Sorry to interrupt my spectacular conversation with Howard Scott Warshaw. I have to phone home real quick. And we're back with Howard Scott Warshaw, going deeper into the ramifications of saying yes to ET. And we're back. I didn't

Howard Scott Warshaw 40:53

realize I was opening the door to ignominiously. Over Over the decades and decades, I also didn't realize he had already called my boss's boss to say, hey, we need an E T game for September 1. And he'd already said, No, you can't do it. You can't do a game if you can't do a video game in five weeks just can't do it. And after that, rakers are still called me directly. And of course, I said absolutely will do it. And I did it. But it's a very different mindset when you talk about the design mindset for what's going on. For one thing coming up with a game for it was kind of tricky, because like I was saying before, like for Raiders of Lost Ark, there's a game, there's a movie that lends itself to a game format. 80 is an emotional tone film, it's not an adventure serial. So where's the game in it? Well, you pick a set piece or something somewhere it was, it was tricky to figure out what it was. And I wanted to make an emotional tone game, which you can't do on the VCs. That's crazy. But I was crazy. That's where I was. But it was also usually when you make a game, what you do is you keep working till it's a good game, and then you release it. It's not about time, it's about quality. With the T It wasn't about making a good game, it was about making a game that could be done in five weeks period, and making that as good as possible. So the good game part took a backseat to the getting it done part. So and I understood that and I designed something that would go in that direction and presented it to Spielberg and eventually got it approved. That's a funny story in the book, how that went through. But it did get there. And then I got to drive myself into the ground for another five weeks, and just completely burned myself out. But I delivered a gun debug game in five weeks.

Jeff Dwoskin 42:34

It's incredible that you were able to pull it pull it off. And I mean, I'm sure you know, just lack of sleep, lack of eating or not, or eating while pretty much everything Yeah, in the book, you describe the release of the T game as you parallel that to the first playable stage of a game.

Howard Scott Warshaw 42:52

Right. And it was I mean, basically what I understood was that I understood that in five weeks, I'm not going to do a full development. You don't you don't plan a six month game and try to do that in five weeks, that's just going to fail what I could do, usually it would take two to three months to get to a first playable version of a game anyway, I just figured what I'll do is I'll try to get the first playable and hope that's it. So there's a conversation that you don't hear very often, which is one person says, Hey, how'd your project go? And the other person goes, Oh, I achieved 100% of my initial design plan. The other person goes, Oh, that's too bad. That's a shame. You never hear that. Right? That sounds like a great success, right? Hey, I did 100% of my intention. The thing is, if you really think about it, really great products, really, really successful products. If you look at the original designs for those products, they usually don't actually resemble each other that much, you know, and on a successful development, your original plan may be represented 20 25% in the final product. The reason is not that you don't do the rest. The reason is the rest of it change because it's better, it actually got better than the original design. And that happens through a process I call a rumination, rumination and reflection time. And I knew there wouldn't be any of that on this thing. It was going to be a death march right from the start. Just go and if I can just get to first playable, but it puts an incredible amount of pressure for the original design to work and to be just right. Because there's no room to look at it, see what's wrong with it like on Yar's Revenge and prayers and tweak it and tune it and fix it. And so that's what happened is I actually achieved virtually 100% of my original design right at five weeks. And yeah, some people like that more than others.

Jeff Dwoskin 44:37

But even even in the telling of the Yar's Revenge story, it's like at at first playable what became ultimately one of the greatest games if not the greatest game of all time. Nobody liked right so if you that story, it ended right there. There may not even be any other stories beyond that because the real truth from what I'm hearing and the story as well, in your in the title of your book, you take credit for killing the industry. It sounds to me like really it was it was just the corporate greed and trying to get everything out for Christmas and breaking every rule that they knew to be true to just meet a deadline that maybe you were if you don't mind me saying stupid enough to accept?

Howard Scott Warshaw 45:20

Oh, absolutely. It was the ultimate act of hubris and ridiculousness. And in point of fact, there was a poignant moment where just a couple of days into the project, I went to a department meeting and they announced that I was doing the EA T game I had just finished Raiders. And they said, okay, so Howard's doing the T game and everybody starts crumbling, oh, Howard gets to et Howard just did Raiders that kind of Howard gets through all the Spielberg title. And so I stood up in the meeting. And I said, Hey, I said, this is this is July 30. I said, Hey, this game is due September 1, anybody who wants it, just raise your hand you got you can have it? Anybody. Crickets, there was nothing, nobody said a thing. And that was the last time anybody complained that I took the T game, right. But instead of saying, oh, Howard gets to do all the titles, what they said was, oh, man, Howard's crazy. This is not going to work. And if it does, it's gonna be a mess. It was an amazing challenge to take on, it was an absurd thing to do. And you're right, the title of the book, you know how I made history by killing an industry. That's how I'm reputed to be, but that title is meant to be ironic. A lot of people say to me, you know, gee, I don't really think you actually killed, I did not kill the video game industry, I want to be clear about that. And I do go at length into the book about all the factors that really did contribute to the industry falling apart at the time that it did. And it wasn't because of ET. But et was not causative in the crash. But et was a symptom of the kinds of things that led to the crash. And I mean, just to sum it up, very briefly, think about the idea that the most expensive by far the most expensive and most valuable license in videogame history was given the shortest development time of any product by a factor of five, why would you go through all that trouble to get a super valuable license, and then put it under that kind of development pressure? It's not because you're thinking clearly and making smart moves, right. But it was that kind of situation is symptomatic of the kind of problems that manifested at Atari and ultimately blew apart the industry.

Jeff Dwoskin 47:26

It's a really interesting, interesting story of just how it just goes to show you like when you really have to be aware of something when it's exploding to be able to control it, because at some point, it's just going to it doesn't continue to explode and grow. You started to you can take advantage of that. And then the taking advantage of that is what led to Activision and imagine, right? You don't treat your employees right, that are making millions of dollars. And all of a sudden, you have the spin off companies. Right, exactly. It's all right. So et comes out. You mentioned earlier, there's returns but you still made it made 4 million cartridges they still sold even after returns over 1.5 million units, right? Absolutely. Some people probably love it, some people, whatever, right? And it's like, at what point then, from 1982, to now we're in between there, I imagined before 2014. But like, where did the internet come in? And all of a sudden, where you were like could sleep at night? Because you're like ET is just kind of mostly in memory. And then the internet says, oh, no, our now rather than y'all fatties, right, that's

Howard Scott Warshaw 48:33

about 9495. The internet's just really starting to get off the ground, and the internet, like, which is another new medium, that point. And then like every new medium, it has no idea what the killer app is, but it is super hungry for content. And so what's the content that really started to emerge early on with the internet in the mid 90s? That was top 10 lists, top five, top six, top seven, top three, bottom six, bottom eight, worst 10? Those were the kinds of things those were everywhere. And one of the targets was video games, of course. Now, when you start talking about of all time and video games, you have to remember that when when I was doing video games in the early 80s, first of all, there was no internet. There was no instant feedback, there was no dropping a game, there was no updating a game, right? When you put a game out, then it went out once and that was it. And you're never going to put out a rev you're never going to have an update. So it's like when you're talking about all time there was no internet. There was also there was a no there was no all time, right? There was no there were no oldies in the early 80s Everything was a new there was no history so it's gonna be a while before there is but then there's the crash and then games revitalized with Sony and Nintendo and all that and Sega and away we go and by the mid 90s. Now people have retrospective we look back at the original the first generation video games, you know with a little nostalgia that 2425 year olds have for when they were 15 or 16, and playing video games. So by then there is there starting to be the illusion of an all time. And so now they're doing the worst all the worst video games, the best video games. And what keeps happening is on the best lists Yar's Revenge keeps showing up. And on the worst lists at keeps showing up. And then in 95, New Media magazine published an article where they said that et was solely responsible for the video game crash of the early 80s. They actually called it out and said the ET game destroy the industry single handedly, 8k a code destroyed a $4 billion industry now that's power. That's so that's when that started. And by 2000, it was really rolling. And then early in the 2000s, you started to hear some of the rumors of like, Oh, they're buried, they buried all those cartridges, millions of cartridges and some cash in the desert somewhere. And there was the speculation and people pretended they found them. And here it was, that led to the urban myth.

Jeff Dwoskin 51:03

And that urban myth, which we won't go into because I want everyone can go watch the movie, Atari game over director Zach pan, which ours, Howard, and it is it's a great telling of that. And you know, it's a great one hour documentary, and you should spend the time if you're listening to this to go do that. I have one other quick question for you. From a pop culture point of view. How was it seeing et and Simpsons episode?

Howard Scott Warshaw 51:27

Oh, it was awesome. It was awesome, you know, of all the places to show up to show up in an ETF I mean, at showed up in a Simpsons episode. It was a tree house of horrors episode I believe, which is probably apropos of Yar's Revenge showed up in Walking Dead and a Walking Dead episode once and that was kind of huge. So like games have made various other media appearances, which feels like a huge success to me. I really, that was awesome. I love seeing that.

Jeff Dwoskin 51:53

That is why you are a rockstar Can you give. I know it's in in the works. But can you give a sick 1/62 update before you go on the Yar's Revenge sequel, I

Howard Scott Warshaw 52:04

can say that of all the things people have done with Yar's Revenge. The one thing no one has really done so far is make a sequel. And there's some reworkings that are coming out. There's Yars reimagine. Yar's recharged. I'm not involved with any of those. But I am currently working on a actual Yar's Revenge sequel that is done by me. For me, for for the Atari world and for the Yar's Revenge legend to start to expand the Yars legend going to be awesome. It's going to have all the intense and exciting visual and audio high stimulus overload you expect from Yars Revenge ONLY WAY more so because now we can do it on systems that are not as limited as 2600. That's amazing.

Jeff Dwoskin 52:45

That will be great. I know a lot of people will be super excited about that. Alright, so Well, let's plug the book one more time. Once upon Atari, how I made history by killing an industry.

Howard Scott Warshaw 52:57

You can find it on Amazon or you can go to once upon atari.com where you could get autographed copies if you'd like also my DVD series my once upon Atari DVD documentary series about working at Atari. It's all there. It's all waiting for you. And the audible version is coming up in the next couple of months. I think they

Jeff Dwoskin 53:15

stopped listening. They just ran off together. Unbelievable. Unbelievable. We're just wrapping up, Howard, thank you so much for spending time with me. I can't thank you enough.

Howard Scott Warshaw 53:24

Jeff. It was awesome. Being here. Thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

Jeff Dwoskin 53:28

I hear you have a certain Yars sign off then I feel like I need to ask Oh, I

Howard Scott Warshaw 53:32

always like to say yours truly, Howard Scott Warshaw. That's me. Because a friend of yours is a friend of mine. There's no question about that. All right,

Jeff Dwoskin 53:41

well, now we're friends of yarn. Okay. I look forward to the expanded Howevers and Yar's Revenge, the sequel and all that good stuff, and everyone get the book. It's amazing. It really is.

Howard Scott Warshaw 53:53

Fabulous. Thank you, Jeff. I really appreciate it.

Jeff Dwoskin 53:56

All right, everyone. That was Howard Scott Warshaw. How amazing was that oral history of Atari 2600 game development, bringing Yar's Revenge Raiders of Lost Ark and EA T to life. There's so many more stories check out Howard Scott Warshaw, his book once upon Atari, how I made history by killing an industry, all the links are in the show notes. It's such a great book. So great. Well, with the interview over I did have me reflecting it's interesting, like the whole idea with the emergence of chat GPT now and where's that going to take us and kind of looking back at a different time in history where technology was emerging and where that took us. So anyway, it was just it was just an interesting kind of parallel to me. Anyway, I hope you enjoyed it. We're at the end of the episode, I can't believe it special. Thanks again to my guest Howard Scott Warshaw, and of course special thanks to all of you for coming back week after week. It means the world to me, and I'll see you next time.

CTS Announcer 54:56

Thanks so much for listening to this episode of Classic conversation. sheds. If you liked what you heard, don't be shy and give us a follow on your favorite podcast app. But also, why not go ahead and tell all your friends about the show? You strike us as the kind of person that people listen to. Thanks in advance for spreading the word and we'll catch you next time on classic conversations.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

About the book: “An intimate view into the dramatic rise and fall of the early video game industry, and how it shaped the life of one of its key players. This book offers eye-opening details and insights, delivered in a creative style that mirrors the industry it reveals. An innovative work from one of the industry’s original innovators.”

Comments are closed.